Giardia is a microscopic protozoan parasite that causes intestinal infection and diarrhea in its hosts (CDC, 2024). In cats and dogs, this infection is called giardiasis, which occurs when the parasite colonizes and multiplies in the animal’s small intestine. Once inside the hosts’ gut, the parasites attach to the intestinal lining and often damage it, leading to maldigestion, malabsorption and ultimately causing mild to severe diarrhea. Giardia infection is quite common in companion animals and in a survey done in the last years estimate that around 10–30% of dogs (and a somewhat lower percentage of cats) may be infected at any given time, with higher rates in puppies and kittens (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). Many pets carry Giardia without showing any illness, but they can still shed the parasite cysts in their feces and potentially infect other animals (Merck Vet Manual, 2021).

Transmission Routes

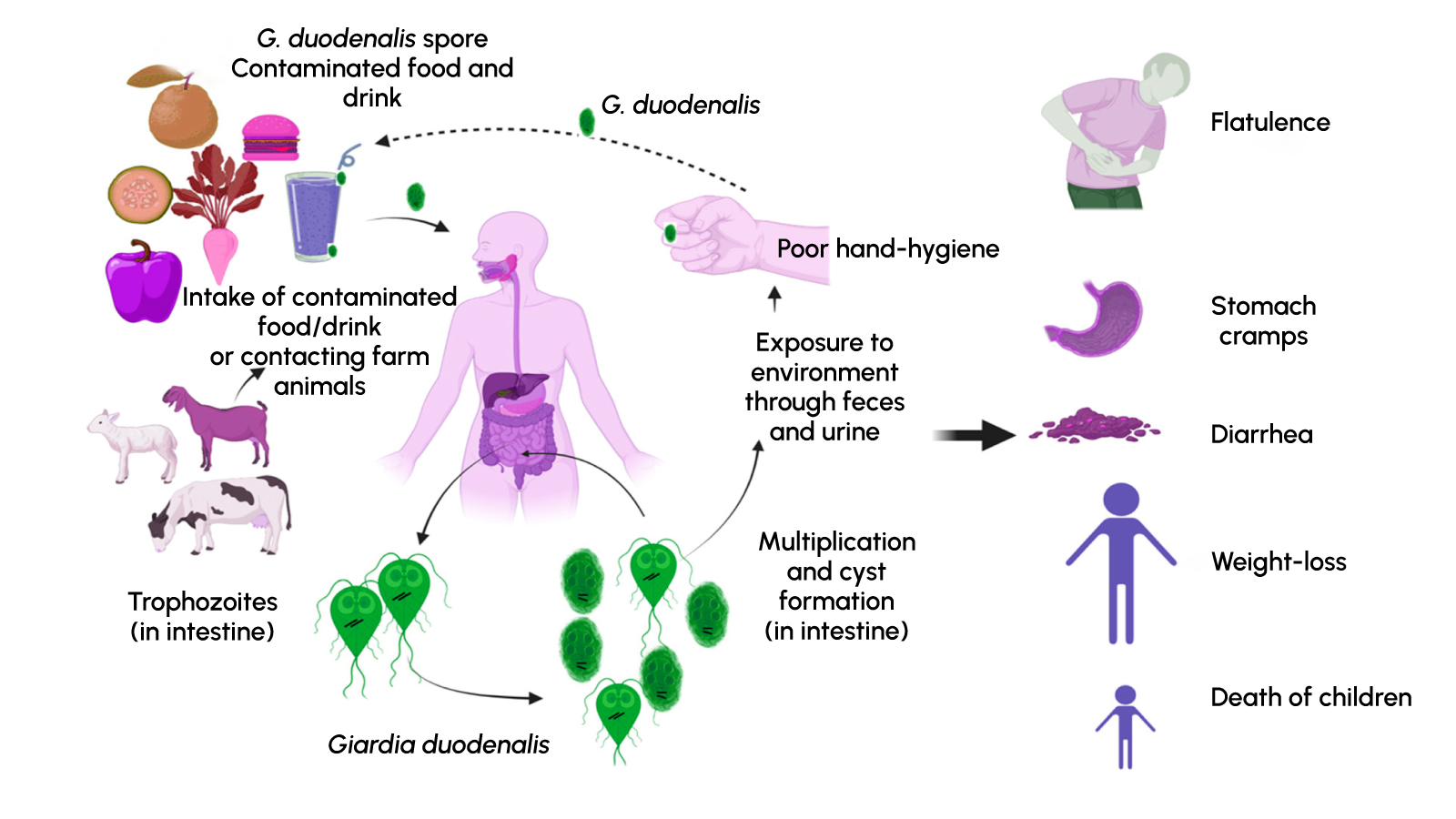

Giardia spreads primarily via the fecal-oral route, meaning an animal (or person) becomes infected by ingesting the parasite’s cyst stage that has been shed in an infected host’s feces (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). Swallowing even small traces of fecal matter from an infected animal can transmit Giardia. For example, a dog might sniff, lick or groom a spot where another dog defecated and ingest cysts (CDC, 2024). Giardia cysts in the environment (in soil, on surfaces, or on objects) can adhere to a pet’s fur or paws. Pets may pick up cysts from contaminated ground (yards, dog runs, litter boxes) or objects like shared water bowls and then ingest them during self-grooming.

Drinking from or swimming in contaminated water is a common route of infection. Puddles, ponds, streams, or any water that has been exposed to feces can harbor Giardia cysts (CDC, 2024).

Giardia can spread quickly among animals—just swallowing a few cysts may be enough to cause infection (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). The risk is particularly high in crowded or unsanitary conditions. Animals in shelters, kennels, catteries, or those that visit communal dog parks have higher infection rates due to greater exposure to contaminated surfaces or water.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

In many adult cats and dogs, Giardia infection is passes usually asymptomatic and hosts’ show no obvious signs of illness (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). However, puppies, kittens, and animals with weaker immunity are more likely to become ill. When giardiasis does cause symptoms, the most common sign is diarrhea which may be chronic or intermittent rather than sudden and severe. Typical characteristics of Giardia-related diarrhea and other clinical signs include soft, greasy, or mucous-laden feces. The stool often appears soft to semi-formed, may have a foul odor, and can contain mucus. It frequently has a shiny or “fatty” look (steatorrhea) because Giardia-induced intestinal damage leads to poor fat absorption (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). Compare to other intestinal parasites, Giardia usually does not cause bloody diarrhea. The feces are more commonly pale or grayish and malodorous, but not bloody. Truly watery diarrhea is less common; stools tend to be soft or cow-pat consistency (Merck Vet Manual, 2021).

Also in some of the cases, some pets will vomit or show nausea during Giardia infection. Vomiting is reported more often in severe or acute cases, but is generally an infrequent sign (Merck Vet Manual, 2021).

Over time, an infected animal may lose weight or show poor body condition due to nutrient malabsorption. Young animals with giardiasis might not gain weight as expected, and their coats may appear duller than normal (Merck Vet Manual, 2021).

Owners should be aware that many Giardia-positive pets show no clinical signs at all. Even if a cat or dog isn’t visibly sick, it might still be shedding Giardia cysts in its feces. Whenever a pet develops persistent diarrhea or unexplained weight loss, Giardia is one of the potential causes that should be considered and investigated by a veterinarian.

Zoonotic Potential: Risk to Humans

Giardia has multiple strains (called assemblages) that tend to infect specific host species (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). The strains of Giardia that infect cats and dogs are usually different from those that infect humans. In fact, most human giardiasis cases are acquired from other humans or from contaminated water, rather than from pets.

What this means for pet owners is that direct infection from a dog or cat to a person is considered uncommon. Experts have noted that Giardia infection from a dog or cat source has never been conclusively documented in North America, and canine-specific strains are not known to infect healthy human hosts (CAPC, 2025). In other words, the average person is unlikely to get Giardia from their pet. However, it is not impossible. On rare occasions a pet may harbor a strain that is infectious to people or a pet’s fur could carry cysts picked up from the environment. Therefore, people with compromised immune systems or underlying illnesses should take extra care when handling Giardia-infected pets (CAPC, 2025). Even for healthy individuals, practicing good hygiene like washing hands after picking up dog waste or cleaning the litter box is an important precaution to eliminate any minimal risk (CDC, 2024).

Environmental Resilience of the Parasite

A key challenge with Giardia is the hardiness of its cysts in the environment. Once shed in feces, Giardia cysts can remain infectious for a long time. They survive for weeks to months in cool, moist conditions (for instance, in cold water or damp soil) (CDC, 2024), and can even tolerate some amount of freezing (CFSPH). On the other hand, these cysts die much more quickly in hot, dry conditions. They are highly susceptible to dehydration and direct sunlight, which eventually destroy them (CFSPH).

Giardia cysts are also tough against many cleaning agents. The cyst’s protective outer shell makes it resistant to common disinfectants. For example, ordinary chlorine bleach or quaternary ammonium cleaners do not reliably kill Giardia cysts (CDC, 2024). Also, outdoor areas contaminated with Giardia (such as grass, soil, or puddles) are especially difficult to sanitize.

Screening and Diagnosis

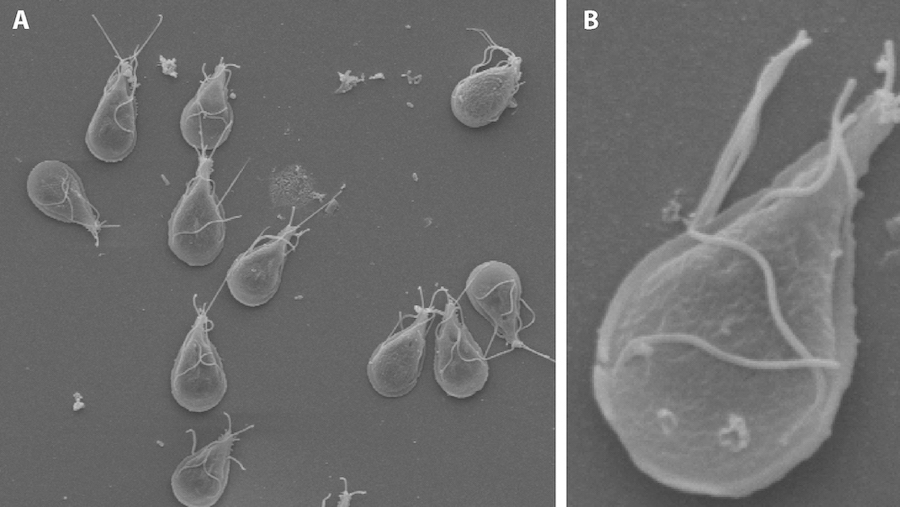

Giardiasis in pets is diagnosed by detecting the parasite or its antigens in the animal’s feces. Veterinarians typically use one or both of two main approaches: A stool sample is analyzed under the microscope to look for Giardia cysts (and occasionally the motile trophozoites). Often, the sample is prepared with a special flotation technique that concentrates cysts to improve detection (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). Identifying the cysts can be tricky – they are tiny and may not appear in every fecal sample – but a trained technician can often spot them if present.

A biochemical test (such as an ELISA “snap” test) detects Giardia proteins in the feces. This Giardia antigen test can confirm an infection even when cysts are not seen under the microscope.

In-clinic rapid tests – usually lateral-flow immunoassays – that deliver results in about ten minutes from a small fecal sample. Studies show modern rapid kits match or exceed microscopy in sensitivity while giving on-the-spot answers.

Many veterinarians will perform a combination of tests to ensure an accurate diagnosis, especially if a pet has consistent symptoms of giardiasis. Because Giardia cysts may be shed intermittently, the vet might request multiple stool samples collected over several days (often 3 samples on 3 different days) to increase the chance of detection (Merck Vet Manual, 2021). Using these screening methods, a veterinarian can definitively diagnose a Giardia infection in a pet.

Preventive Measures

Preventing Giardia in cats and dogs – and stopping it from spreading – requires good hygiene and management practices. Pet owners can reduce the risk of infection by cleaning up their pet’s feces quickly and dispose of it properly (in a sealed bag in the trash). Giardia cysts in feces can contaminate the environment, so removing stool daily from yards, litter boxes, or kennels greatly reduces the chance of exposure for other animals (CDC, 2024).

Washing the pet’s living areas and items regularly also helps. Food and water bowls, litter boxes, bedding, and toys should be cleaned with soap and hot water frequently. Hard surfaces (floors, crates, etc.) can be sanitized with a vet-recommended disinfectant or steam cleaner, and should be allowed to dry completely afterward – thorough drying helps kill Giardia cysts (CFSPH). Note that outdoor areas like soil or grass are impossible to fully disinfect (even bleach won’t reliably kill Giardia in dirt) (CDC, 2024), so focus on removing feces and keeping such areas as dry as possible.

Provide plenty of fresh, clean drinking water for your pets, and do not let them drink from or swim in stagnant or untreated water sources that could be contaminated with feces (such as puddles, ponds, or streams) (CDC, 2024).

If your pet is diagnosed with Giardia, give them a thorough bath to remove any clinging cysts from their fur (especially around the hind end) (CFSPH). This helps prevent the animal from re-ingesting the parasite during grooming and reduces contamination of the home. To add to that, keep them away from communal pet areas until they have fully recovered. Avoid dog parks, pet daycare, or group playdates during the infection period to prevent spreading cysts. Also, do not introduce new, susceptible animals (e.g. young puppies or kittens) into your household or yard until the infected pet is confirmed clear and the environment has been cleaned (CDC, 2024).

Protect yourself and your family by practicing good hygiene when handling pets. Always wash your hands after picking up dog waste, cleaning the litter box, or touching soil that animals use (CDC, 2024). If you are cleaning up diarrhea or soiled areas, wear gloves and use an appropriate disinfectant. By keeping yourself clean, you also protect your pets – you won’t accidentally carry Giardia (or other germs) back to them on your hands or clothes.

In addition to these measures, routine veterinary care is important. Regular fecal examinations (as part of annual check-ups) can screen for Giardia and other parasites early. If your veterinarian identifies a Giardia infection, they will advise you on treatment and how to disinfect your pet’s environment to prevent re-infection.

References

Adam, R. D. (2021). Giardia duodenalis: Biology and Pathogenesis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 34(4), e00024-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00024-19

Sangkanu, S., Paul, A. K., Chuprom, J., Mitsuwan, W., Boonhok, R., de Lourdes Pereira, M., … & Nissapatorn, V. (2022). Conserved Candidate Antigens and Nanoparticles to Develop Vaccine against Giardia intestinalis. Vaccines, 11(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11010096

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). About Giardia and Pets. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/giardia/about/about-giardia-and-pets.html

Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC). (2025). Giardia Guidelines. Retrieved from: https://capcvet.org/guidelines/giardia/

Merck Veterinary Manual. (2021). Giardiasis in Animals. Retrieved from: https://www.merckvetmanual.com/digestive-system/giardiasis-giardia/giardiasis-in-animals

Center for Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH). Giardiasis: General Information and Control. Retrieved from: https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/DiseaseInfo/notes/Giardiasis.pdf