Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a common bacterium in the intestines of cattle, and most of the time it behaves itself. In fact, the majority of E. coli strains are harmless gut residents, the microbial equivalent of good neighbors. However, as every farmer knows, one bad apple can spoil the bunch. Certain strains of E. coli have evolved to be troublemakers that cause disease in cattle or even pose risks to humans.

E. coli Strikes the Young

When E. coli causes illness in cattle, it’s usually in newborn calves. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is a prime cause of neonatal calf diarrhea. These bacteria attach to the lining of a calf’s small intestine and release toxins, resulting in profuse, watery diarrhea within days of birth. An affected calf can dehydrate quickly and go into shock if not treated and to keep in mind it’s a life-threatening situation. Fluid therapy (electrolytes) is essential to save the calf. Fortunately, vaccines are available to prevent ETEC scours. Many farms vaccinate cows late in pregnancy against the E. coli K99 antigen, so they pass protective antibodies to the calf through colostrum (first milk). This approach has made K99 E. coli outbreaks far less common. Ensuring every calf gets ample colostrum is another crucial preventive step, giving the newborn a head start against infection.

Carriers and Zoonotic Risk

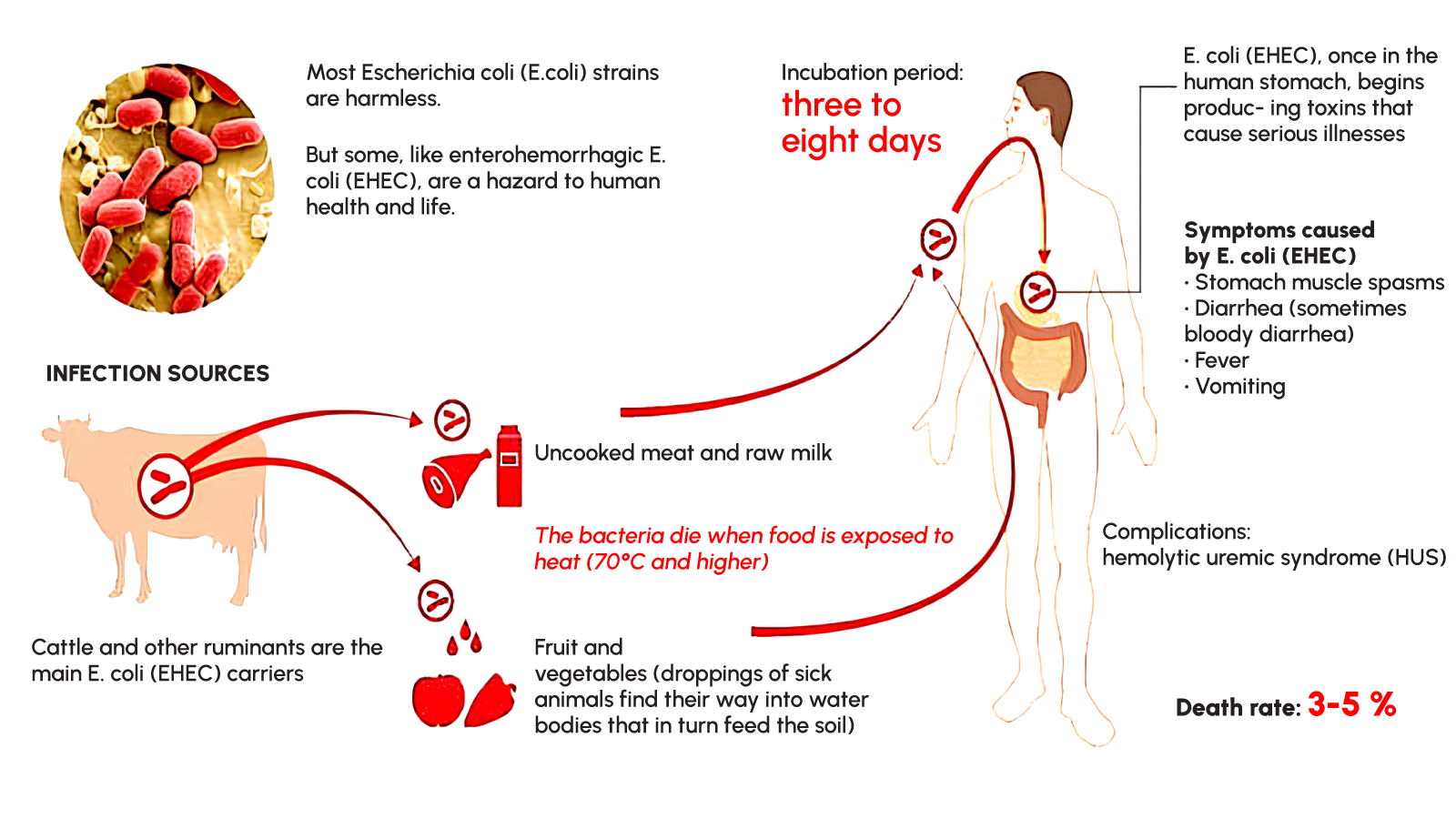

Adult cattle rarely show symptoms from E. coli, but they can harbor some infamous strains. The best-known is Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) O157:H7 – a germ that doesn’t make cattle sick but can cause severe illness in people. Cattle effectively act as silent carriers or reservoirs for these pathogens. Humans unlucky enough to ingest STEC (for example, via undercooked beef or contaminated produce) may develop bloody diarrhea and a dangerous complication called hemolytic uremic syndrome (kidney failure). It only takes a tiny dose to infect a person. E. coli O157:H7 and similar strains typically enter the food chain through fecal contamination: during slaughter (if manure contacts meat) or when fields or water are tainted by cattle manure. Unpasteurized milk is another potential vehicle. Because of this hidden menace, food safety measures are critical. Thorough cooking of ground beef to safe temperatures will destroy E. coli, and proper farm sanitation and meat processing practices can greatly reduce the risk of contamination.

Diagnosing the Culprit

Diagnosing an E. coli infection in a calf requires sorting the bad actors from the crowd of harmless E. coli. Veterinarians often send fecal samples to a lab, where technicians culture the bacteria and identify any pathogenic types (for instance, using special agar that flags E. coli O157). They also use molecular tests: PCR (polymerase chain reaction) can detect genes that produce Shiga toxin or other virulence factors, confirming if an isolated E. coli is a dangerous strain. In addition, rapid immunoassays are available. These include ELISA tests and lateral-flow kits that quickly screen for E. coli antigens or toxins in a fecal sample. Such tests give farmers a speedy heads-up (often within minutes) while awaiting definitive lab results.

Prevention and Control

With E. coli good farm management can prevent many problems before they start. Key steps include strict hygiene in calving areas to minimize calves swallowing fecal bacteria, adequate colostrum intake, and the use of E. coli vaccines for pregnant cows to protect calves. There is currently no commercial vaccine for the O157:H7 type strains in cattle, so reducing those pathogens hinges on cleanliness and proper manure handling on the farm, as well as vigilance during meat processing. On the consumer end, basic food safety habits like cooking meat thoroughly and avoiding raw milk are vital defenses against zoonotic E. coli. By combining efforts on the farm and in the kitchen, we can keep both our cattle and ourselves safe from those few bad apples among the E. coli.

References

Antibiotic for e coli in cats. (2025). Jpabs.org. https://jpabs.org/misc/antibiotic-for-e-coli-in-cats.html

Naylor, J. M. (2009). Neonatal calf diarrhea. Food Animal Practice, 70.

World Organisation for Animal Health. (2023). *Verocytotoxigenic *Escherichia coli (Chapter 3.9.10). In Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (pp. 1-12). World Organisation for Animal Health. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.09.10_VERO_E_COLI.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (2023, March). E. coli on U.S. Beef Cow-calf Operations (NAHMS Beef 2017 Study Information Brief). https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/beef2017-e-coli-us-beef-cow-calf-ops.pdf

Segelken, H. R. (1998, September 8). Simple change in cattle diets could cut E. coli infection. Cornell Chronicle. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/1998/09/simple-change-cattle-diets-could-cut-e-coli-infection