Ask any calf rearer about “crypto” and you will get a knowing look. Cryptosporidiosis is a gut infection caused by Cryptosporidium parvum. It hits calves hard in the first weeks of life, it spreads like Spainsh Flu like its 1918, and it can occasionally make people sick as well. The parasite’s oocysts are tiny, tough, and immediately infectious, so once they get into a pen they can linger unless hygiene and testing are on point.

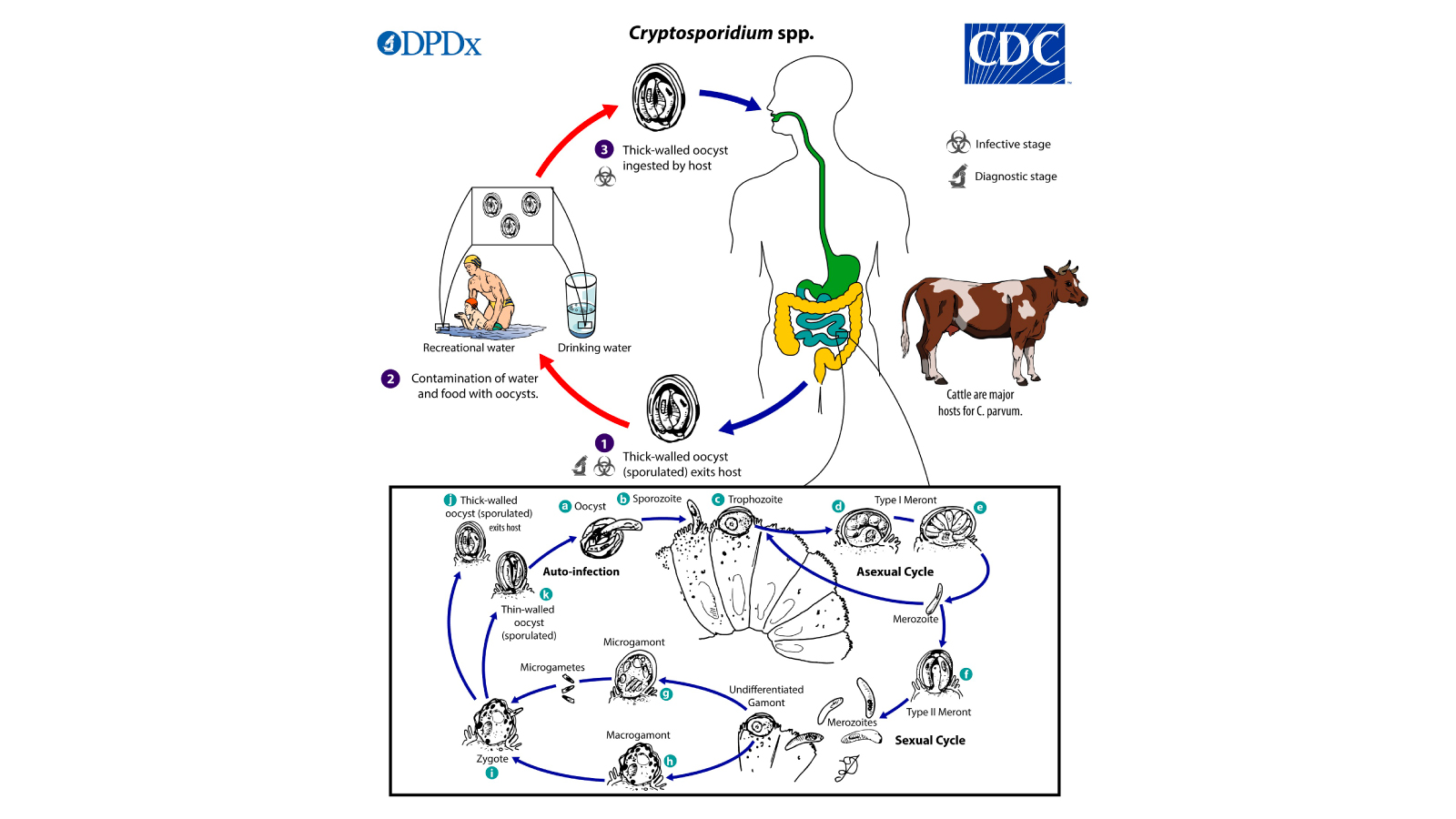

Source: CDC, DPDx, Cryptosporidiosis, June 3, 2024

What It Is and How It Spreads?

C. parvum is a protozoan that invades the small intestine. Infected calves shed millions to billions of oocysts in watery feces. These oocysts survive well in damp bedding and troughs, they tolerate many routine disinfectants, and a low dose can start an infection. Calves pick up oocysts by licking, nursing, or nosing contaminated surfaces, and people can carry them on boots and buckets without realizing it. Autoinfection inside the gut keeps the cycle going, while thick walled oocysts pass into the environment, ready to infect the next calf.

Spotting Sick Calves, Keeping People Safe

Most cases strike at 7 to 14 days of age. The classic picture is pale yellow, watery diarrhea with mucus, dehydration, sunken eyes, poor suckle, and slow weight gain. Co-infections with rotavirus, coronavirus, or enterotoxigenic E. coli can make scours worse. Cows and older calves often look fine, yet they can still shed oocysts and seed the environment. Because C. parvum is zoonotic, farm families, veterinarians, and visitors should take care of themselves, especially young children, pregnant people, the elderly, and anyone immunocompromised. In humans the illness usually causes self limited watery diarrhea and cramps, although prolonged illness can occur in vulnerable groups.

Prevention on the Farm

There is no silver bullet treatment, which means prevention carries the day. Give every calf clean colostrum quickly after birth, manage stress and overcrowding, and separate sick calves from newborns. Keep pens dry, scrape and remove manure often, and use all in, all out housing so you can empty, clean, and allow time to dry between batches. Heat, drying, and sunlight are your friends. Wash feeding bottles and tubes with hot water and detergent, keep feed and water clean, and control rodents and birds around calf areas. Staff should use dedicated boots and coveralls for calf sheds, wash hands after handling scouring calves, and avoid tracking muck into common areas. On mixed farms, set a simple rule, clean work first, dirty work last, then wash up.

Testing and Detection, From Barn to Laboratory

Clinical signs point the way, yet laboratory testing confirms the culprit and helps you act fast.

Microscopy with a modified acid fast stain can show classic round oocysts in fecal smears. It is inexpensive and useful when performed by trained eyes, although sensitivity varies with shedding. Antigen detection by ELISA or direct fluorescent antibody testing brings higher sensitivity in many labs and works on fresh or preserved stool.

Rapid lateral flow tests add speed and simplicity on farm. A small fecal extract is placed into a cassette, and a clear positive or negative appears within minutes. These point of care strips help veterinarians and producers decide quickly on isolation and hygiene measures. They are screening tools, so follow up in the lab is wise during outbreaks or when results will inform herd level decisions.

Polymerase chain reaction has become the reference for confirmation, since it detects parasite DNA even when oocyst counts are low. Real time PCR and multiplex gastrointestinal panels can identify C. parvum alongside other calf scour agents and can differentiate Cryptosporidium species when needed for epidemiology. Turnaround from many veterinary labs is now measured in hours rather than days, which keeps control measures one step ahead of spread.

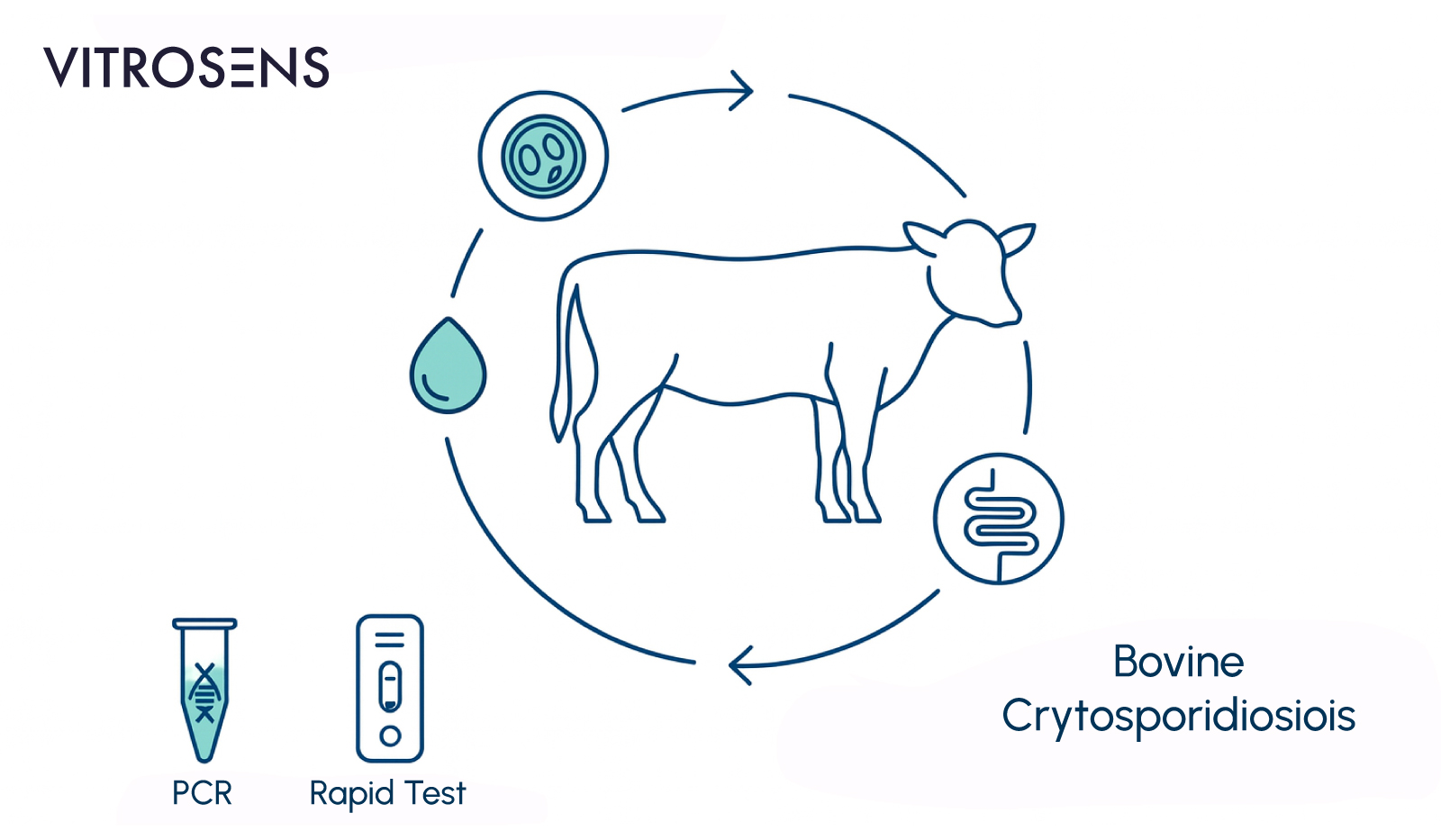

Vitrosens Perspective, Kits That Accelerate Decisions

Early answers change outcomes. Vitrosens focuses on practical, reliable detection, so farms and vets can move from suspicion to action without losing the day. For first line screening, a rapid immunochromatographic test for Cryptosporidium antigen in calf feces delivers a simple yes or no result at the pen side, which supports immediate isolation, cleaning, and supportive care. For confirmation and surveillance, laboratory PCR solutions that target conserved Cryptosporidium genes provide sensitive detection and can be integrated into broader calf diarrhea panels. Used together, rapid screening in the barn and PCR in the lab create a one two punch, fast triage on site, definitive confirmation in the lab.

One Health Approach Means Early Action

Crypto reminds us that animal and human health share the same barn door. When scours appear in young calves, act early, collect stool from a few affected calves, run a rapid test, and send samples for confirmatory PCR. Tighten hygiene the same day, not next week. That rhythm, test early and clean often, protects calves, prevents barn wide contamination, and reduces the chance of human illness. Good habits go a long way, clean boots, clean bottles, clean hands, and a quick test when the first calf scours. With sensible prevention and modern diagnostics, the tiny parasite loses its big advantage.

References

- Thomson, S., Hamilton, C.A., Hope, J.C. et al.Bovine cryptosporidiosis: impact, host-parasite interaction and control strategies. Vet Res48, 42 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-017-0447-0

- https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/cryptosporidiosis/

- https://www.woah.org/en/disease/cryptosporidiosis/

- https://aphascience.blog.gov.uk/2024/02/29/cryptosporidium/

- https://www.merckvetmanual.com/digestive-system/cryptosporidiosis/cryptosporidiosis-in-animals

- https://afs.ca.uky.edu/content/preventing-cryptosporidiosis-commonly-called-crypto-dairy-calves