In recent years, avian flu outbreaks have hit poultry farms across the globe, causing significant economic losses, threats to public health, and serious challenges for the poultry industry. Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, is a viral disease that primarily affects birds, with varying degrees of impact on humans. In this blog, we will delve into the causes, consequences, and preventive measures of avian flu outbreaks in poultry farms.

Understanding Avian Influenza

Avian influenza is a highly contagious viral disease that can infect a wide range of birds, including chickens, ducks, turkeys, and other poultry [1]. The virus is categorized into two groups based on its pathogenicity:

Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI): These strains of avian flu typically cause mild symptoms or go unnoticed in infected birds. However, LPAI can mutate into a highly pathogenic form [1].

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI): HPAI strains are more virulent and can cause severe illness and high mortality rates in poultry. They also pose a greater risk to humans.

Symptoms of Avian Influenza in Birds

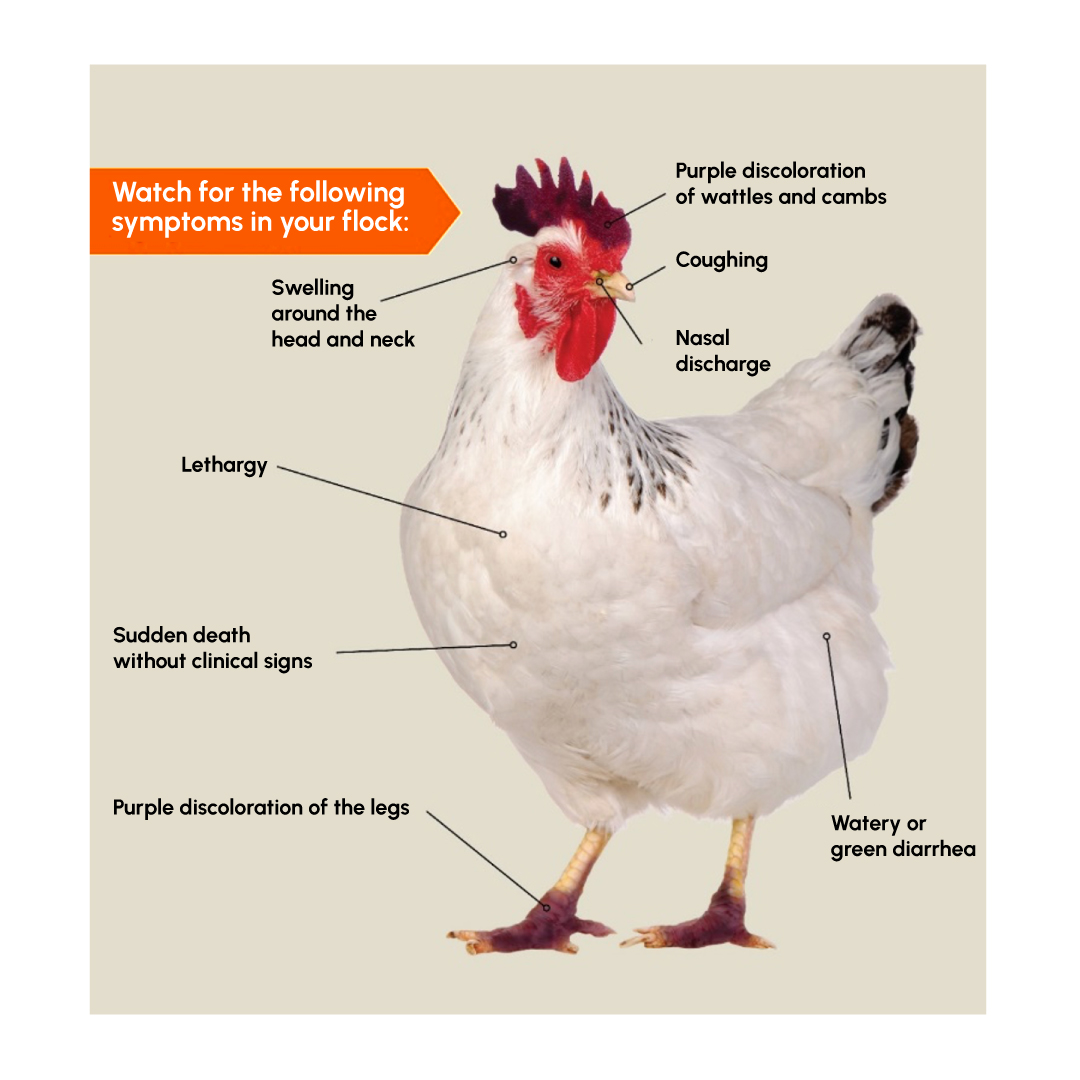

The symptoms of avian influenza in birds can vary depending on the strain of the virus and the species of bird. Common signs of avian flu in poultry include:

Respiratory Distress: Infected birds may exhibit difficulty breathing, coughing, and sneezing.

Swelling and Discoloration: Swelling of the head, neck, and eyes, along with a change in the color of the comb and wattles, are common symptoms.

Decreased Egg Production: Laying hens may experience a significant drop in egg production, often with a decline in egg quality.

Nervous System Signs: In some cases, affected birds may show signs of nervous system dysfunction, such as paralysis, tremors, and uncoordinated movements.

Sudden Deaths: Highly pathogenic avian influenza strains can lead to sudden and significant mortality within the flock.

Causes of Avian Flu Outbreaks

Wild Birds: Wild waterfowl like ducks and geese are natural carriers of avian influenza viruses [3]. They can transmit the virus to domestic poultry through direct contact or by contaminating the environment with their droppings.

Bird-to-Bird Transmission: Once avian flu enters a poultry farm, it can spread rapidly among the birds. Infected birds shed the virus in their feces, saliva, and nasal secretions, allowing it to be transmitted through close contact [3].

Contaminated Equipment and Personnel: The virus can be carried into farms on contaminated equipment, clothing, and footwear. Proper biosecurity measures are essential to prevent its introduction.

Real-Life Examples of Avian Flu Outbreaks

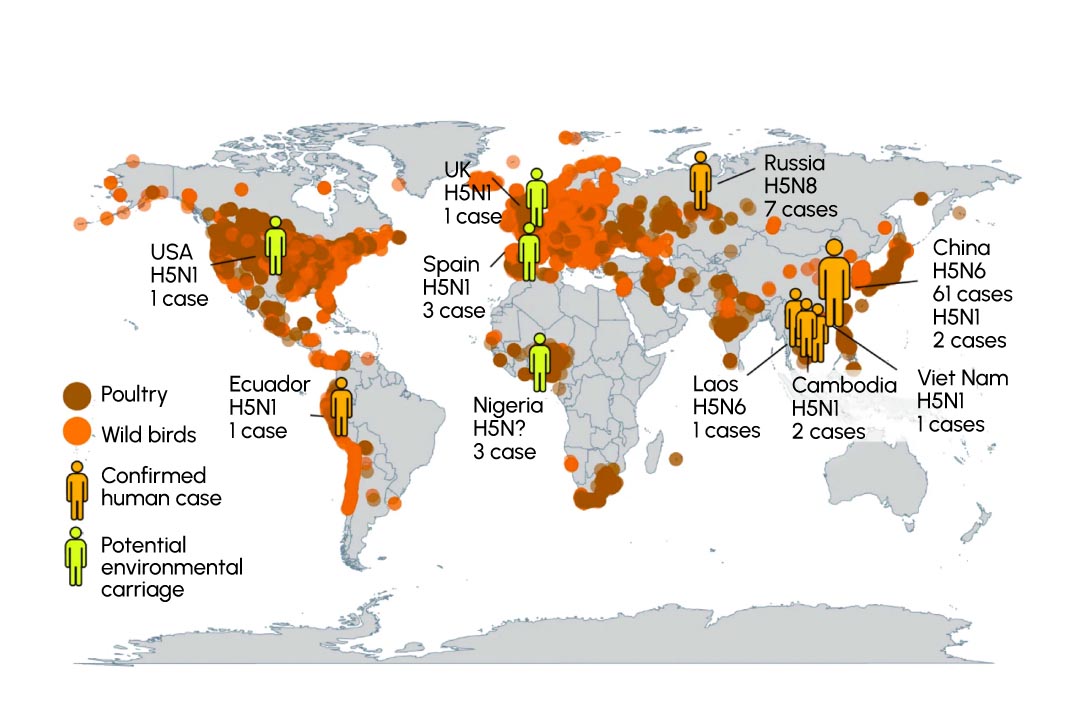

Vietnam, 2003: Vietnam experienced one of the earliest recorded human cases of avian influenza caused by the H5N1 strain. This raised global concerns about the virus’s potential to infect humans.

Nigeria, 2006: Nigeria reported its first avian influenza outbreak in commercial poultry farms. The government initiated a mass culling of birds to control the outbreak.

The 2015 U.S. Outbreak: Between 2014 and 2015, the United States faced its most extensive H5N2 avian influenza outbreak, leading to the depopulation of around 51 million birds to manage the disease [4]. From May to June 2015, a staggering 25 million birds were culled in just two months, averaging around 409,836 birds per day, or 284 birds every minute [4]. This outbreak resulted in public expenditures of $879 million and inflicted over $3 billion in losses on the U.S. egg and poultry industry, making it the most expensive High-Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) outbreak in U.S. history [4].

Europe, 2016-2017: Several European countries, including France, Hungary, and the United Kingdom, faced avian influenza outbreaks during this period. Thousands of birds were culled to prevent further spread.

2020 Avian Flu Outbreak: By the end of 2020, several outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) were reported in various European countries. These outbreaks, primarily affecting wild birds, were detected in countries such as Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United Kingdom [5]. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) identified three HPAI virus variants, A(H5N8), A(H5N5), and A(H5N1), with A(H5N8) being the most prevalent [5]. In response to these outbreaks, significant measures were taken, such as the culling of thousands of chickens in Germany and the discovery of H5N5 in a Belgian poultry farm, leading to the culling of a large number of birds [5].

United States 2022–23 Outbreak: The United States has been grappling with a bird flu outbreak since early 2022, resulting in the death of over 58 million birds across 47 states. These birds either succumbed directly to the bird flu virus or were culled due to potential exposure to infected birds [6]. The outbreak has incurred a substantial cost of $661 million for the government, despite rigorous mitigation efforts implemented by the poultry industry after the 2015 outbreak [6]. Iowa, the largest egg producer in the country, has been the hardest hit, with nearly 16 million birds culled. Additionally, in January 2023, significant price disparities for eggs were observed at the border, where a dozen eggs cost $2.30 in Tijuana and $7.37 in California, leading to inspection station regulations prohibiting the transportation of eggs across the border [6].

Africa 2023 Outbreak: In March 2023, Senegal reported an avian influenza outbreak on a poultry farm in the village of Potou, near Louga in the northwestern part of the country. The outbreak resulted in the death of 500 birds at the Potou farm and 1,229 bird fatalities in Langue de Barbarie Park and its vicinity [7]. A week later, H5N1 bird flu was detected in a wild bird reserve in Gambia. Subsequently, during September and October 2023, South Africa experienced one of its most severe bird flu outbreaks, leading to the culling of millions of chickens. This outbreak disrupted poultry meat supplies and caused shortages of eggs in supermarkets across the country.

How to Use Avian Influenza Rapid Antigen Test Kit?

Using an Avian Influenza Rapid Antigen Test Kit is a valuable tool for the early detection of avian influenza in poultry. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to use such a kit:

Materials Needed:

- Avian Influenza Rapid Antigen Test Kit

- Sample collection swabs

- Sample collection tubes

- Disposable gloves

- Timer or stopwatch

- Clean, disinfected work surface

Instructions:

- Read the Manufacturer’s Instructions: Start by thoroughly reading and understanding the manufacturer’s instructions provided with the test kit. Different kits may have slight variations in their procedures.

- Prepare the Work Area: Ensure that you are working in a clean and disinfected area to avoid contamination. Wear disposable gloves to prevent the transfer of any infectious material.

- Collect the Sample:

- Select the birds that you suspect might be infected with avian influenza. Ideally, choose birds that exhibit symptoms consistent with avian flu.

Carefully collect swab samples from the respiratory and cloacal areas of the birds. Use a separate swab for each bird to avoid cross-contamination. Follow aseptic techniques during sample collection

- Prepare the Sample:

- Place each swab in the sample collection tubes provided with the kit.

- Add the appropriate reagents or solutions provided with the kit into the tubes, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

- Incubation:

- Allow the sample to incubate for the specified duration indicated in the kit’s instructions. This period may vary among different test kits but typically ranges from 10 to 15 minutes.

- Prepare the Test Strips:

- Open the test strip pouches provided with the kit immediately before use.

- Carefully place a few drops of the incubated sample onto the test strip’s sample well. Use a separate strip for each sample.

- Read the Results:

- Observe the test strips for the presence of test and control lines after the specified incubation time. The test lines indicate the presence of the H5N1 avian influenza virus.

- Interpret the results based on the manufacturer’s guidelines. Typically, a visible test line next to the control line indicates a positive result, while the absence of a test line suggests a negative result. Faint test lines may also indicate a positive result and should be considered as such.

- Document the Results:

- Record the test results for each sample. Note the sample identification and whether the result is positive or negative.

- Dispose of Materials:

- Safely dispose of used gloves, swabs, and test strips according to biohazard disposal guidelines. Follow any additional disposal instructions provided by the manufacturer.

- Notify Authorities:

- If any of the samples tested positive for avian influenza, notify the relevant local or national authorities responsible for disease control in poultry. Follow their guidance on containment and control measures.

Remember that using a rapid test kit for avian influenza is a critical step in early detection and containment of the virus. Proper and timely identification of infected birds can help prevent the further spread of the disease and protect both poultry populations and public health. Always follow the specific instructions provided with the test kit, and consult with local health and agricultural authorities for guidance on avian influenza control measures.

REFERENCES

[1][2] Lycett, S. J., Duchatel, F., & Digard, P. (2019). A brief history of bird flu. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 374(1775), 20180257.

[3] Dhama, K. (2013). Avian/Bird Flu virus: poultry pathogen having. J Med Sci, 13(5), 301-315.

[4] Jacobs, Andrew (24 February 2022). “Avian Flu Spread in the U.S. Worries Poultry Industry”. The New York Times. paragraph 16. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

[5] Lee, Bruce Y. “Avian Influenza, H5N8, Spreading Rapidly In Europe, What To Do About The Bird Flu”. Forbes. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

[6] CDC (2022-11-03). “U.S. Approaches Record Number of Avian Influenza Outbreaks”. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2023-01-13.

[7] “Senegal reports outbreak of H5N1 bird flu on farm, WOAH says”. Reuters. 2023-03-31. Retrieved 2023-04-10.