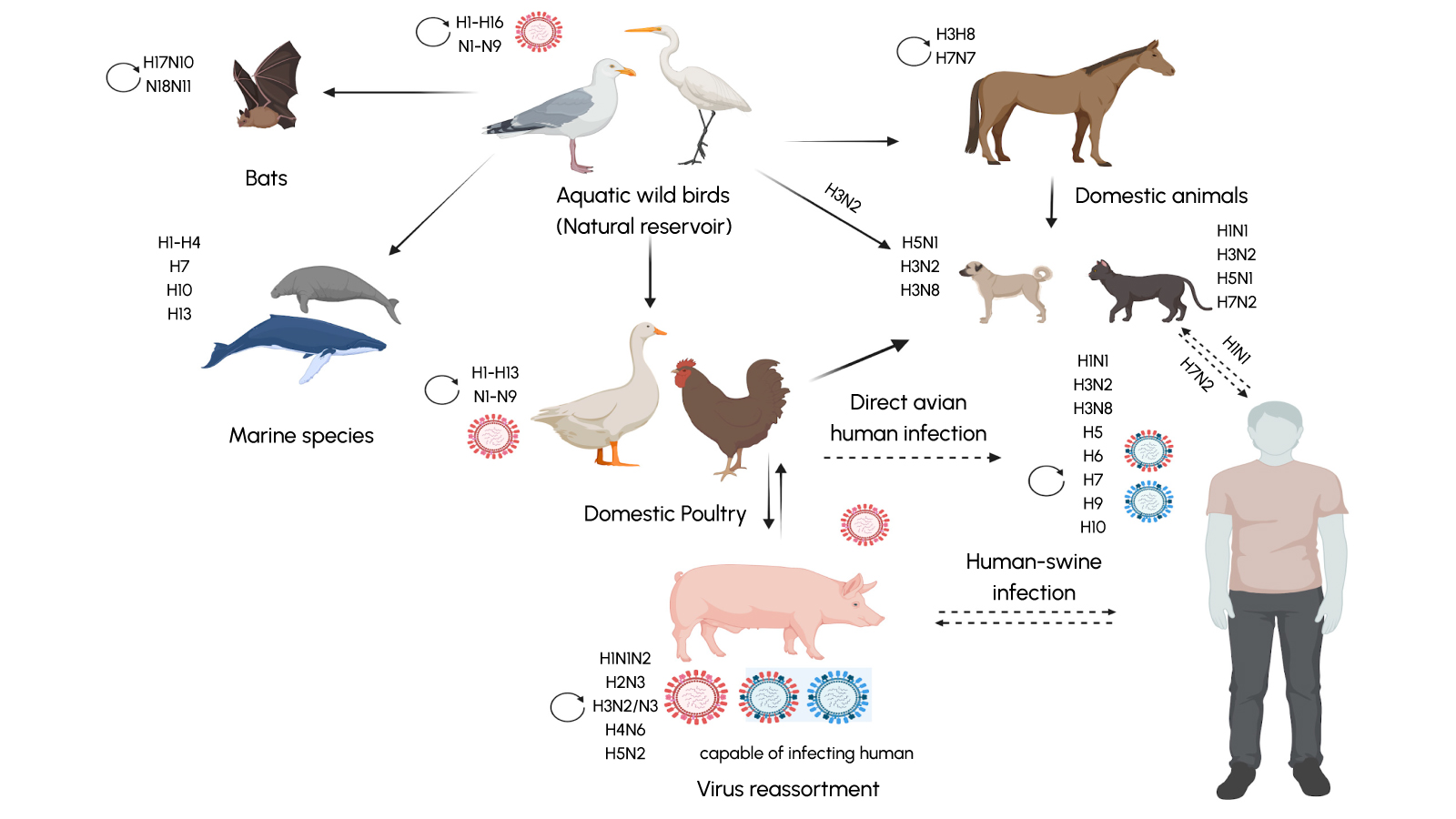

Bird flu (avian influenza) isn’t a brand new bug, it’s a family of influenza A viruses that normally circulate in birds. Wild waterfowl (ducks, geese, shorebirds) are the classic reservoir hosts, often carrying flu viruses without looking sick. But some strains can spill into farm flocks or even people. For example, the highly pathogenic H5N1 strain (clade 2.3.4.4b) has swept across the globe since 2022 and even appearing in dairy cows, cats, and wild mammals. H7N9 (another H5 family relative) made headlines in March 2025 with the first US outbreak in commercial chickens since 2017. In short, these bird flus can fly far, which is why scientists keep a close eye on them.

Source: AbuBakar et al., 2023, Viruses 15(4):833. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15040833

How Bird Flu Spreads (and Jumps to Us)?

Avian influenza viruses move through bird populations much like mischievous hitchhikers. An infected bird sheds virus in its saliva, mucus and droppings, so healthy birds can catch flu by pecking at contaminated feed, water or perches. Waterfowl are especially good at moving the virus, migrating flocks can pick it up in one wetland and carry it thousands of miles on their annual routes. On farms and in live markets, the virus can “hitchhike” on anything porous: muddy boots, shared waterfowl, trucks and even vet equipment can carry virus between barns. Poor biosecurity (for example, not cleaning cages or feeding gear between groups) is a common way outbreaks spread.

Spillover to humans is uncommon but real. Almost all documented human cases of H5N1 or H7N9 have been linked to very close contact with infected birds or their environments (slaughtering, defeathering, or visiting live bird markets). The virus isn’t yet good at infecting people; to date no sustained human to human spread has been seen. In short, bird flu is mainly a disease of birds, but it can rarely hop the species barrier when people get a front row seat to the poultry show.

Spotting Sick Birds (and People)

Clinical signs in birds depend on the strain’s virulence. Low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) often causes only mild symptoms or none at all. A flock might see just a few birds sneezing, a slight drop in egg production, or a momentarily duller chicken. High pathogenic strains (HPAI), however, hit like a thunderclap. Entire flocks can die suddenly, even with no prior coughing or sneezing. Surviving birds may hang their heads, lose appetite and appear lethargic. A classic red flag is unusual coloration: wattles, combs or legs may swell and turn purple or blue (a telltale sign of poor circulation). You might also spot nasal discharge, watery eyes, coughing or sneezing, and diarrhea. Egg production usually plunges and eggs may be soft shelled or deformed.

In birds Mild strains few signs (maybe a sneeze or loose egg). Bad strains sudden deaths, swelling/purp le spots on combs/wattles, droopy birds, runny noses, and sharp drops in eggs.

In people the picture is usually milder but can be serious. Human avian flu cases mostly look like a flu or eye infection. Fever, chills, cough, sore throat and body aches are common, and many cases report conjunctivitis (red, irritated eyes). For instance, recent U.S. H5N1 cases involved mild flu symptoms and sometimes eye redness. Globally, human infections with H5N1 and H7N9 have been reported roughly 900 people have caught H5N1 since 2003 (about half died), and over 1500 caught H7N9 (many fatal) in China. These numbers underscore why doctors take bird flu seriously, even if human risk remains low.

Testing and Prevention: Keeping the Virus at Bay

Veterinarians test for avian influenza by swabbing or taking tracheal/cloacal samples from sick or dead birds, then running lab PCR or virus isolation tests (samples go to state or USDA labs). In practice, farmers and vets look for outbreaks by monitoring flocks closely and sending samples if birds look sick.

On the farm good biosecurity is the best shield. There are a few ways to protect the hosts. One of them is keep chickens and other poultry indoors or netted to prevent contact with wild waterfowl. Other one is restrict visitors, vehicles and movement of birds/equipment between pens. Disinfect boots and tools; clean cages and feeders after each use. Also don’t introduce new birds of unknown health into a flock. Quarantine any newcomers for a few weeks if possible. Safely disposable dead birds (or those that need culling), and dispose of carcasses, manure and litter hygienically is also carries a great deal. To add to that, in regions where vaccines are approved, vaccinating poultry can dramatically reduce viral spread and flock deaths.

Precautions focus on avoiding the virus entirely. If you work with birds, wear gloves, masks and eye protection when handling sick or dead poultry. Never eat or cook raw poultry, eggs or unpasteurized dairy from sick animals. Always thoroughly cook poultry and eggs (to an internal temp of approxmately 74°C) and pasteurize milk. Wash hands and equipment after handling birds or eggs. Finally, report any suspicious outbreak of illness or unusual deaths in birds to veterinary authorities immediately! Early detection helps stop it.

One Health and Early Action

Bird flu is the epitome of a One Health issue: the same virus can infect flocks, pets, wildlife and people. Experts urge a “coordinated, interagency multisectoral” response to outbreaks. In practice this means farmers, wildlife managers and public health officials sharing information. Quickly culling or vaccinating affected flocks, boosting surveillance in wild birds, and informing hospital labs to test flu like illness for avian strains are all part of the mix. Critically, avian influenza is notifiable: any suspected case in poultry (or certain wild birds) must be reported to veterinary authorities. This kind of rapid reporting and action has stopped many outbreaks from becoming epidemics.

The bottom line is avian influenza may start in a henhouse, but unchecked it can flit across species and borders. By acting early through vigilant monitoring, farm biosecurity, vaccination where appropriate, and public awareness we can keep this feathered foe grounded. After all, what’s good for the birds often keeps us flying safely too.

References

AbuBakar, U., Amrani, L., Kamarulzaman, F. A., Karsani, S. A., Hassandarvish, P., & Khairat, J. E. (2023). Avian influenza virus tropism in humans. Viruses, 15(4), 833.

https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-health/avian-influenza

https://www.cdc.gov/bird-flu/index.html

https://www.woah.org/en/disease/avian-influenza/

https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/influenza-h5n1