What is Infectious Bronchitis and Which Birds Does It Affect?

Infectious bronchitis (IB) is a highly contagious respiratory disease of chickens caused by the avian coronavirus IBV. It occurs worldwide and affects both meat-type and egg-laying chickens of all ages. Infected flocks suffer rapid spread of disease. While IBV primarily infects domestic chickens, related coronaviruses have been found in other birds (pheasants, quail, partridges, etc.). However, chickens are the most important natural host for IBV. The virus attacks the respiratory tract, and in egg-laying hens it can also infect the reproductive system.

What are the Symptoms of IBV in Birds?

Infected chickens show signs of respiratory illness and production losses. Onset is fast and the morbidity (sickness) rate approaches 100%. Common symptoms include:

Sneezing, coughing, nasal discharge, and sneezing are often seen. Watery eyes or “rales” (wheezing sounds) in the trachea may occur. Birds may breathe with open mouths or gasp for air when breathing is hardextension.msstate.edu. Infected chicks appear listless and huddle for warmth. They eat and drink less, so weight gain slows. Feathers may look ruffled and birds can become dehydrated. Egg-laying hens often show a sharp drop in production (egg laying can fall by up to 70% in an outbreak). Eggs that are laid may have thin, soft, misshapen or rough shells, and watery egg whites. Even after recovery, egg production may take weeks to return to normal. In young hens, IBV infection can permanently damage the oviduct, causing a “false layer” condition where a hen does not lay eggs despite mature ovaries.

Some IBV strains attack the kidneys. Affected birds develop increased thirst and produce very wet, white droppings. These birds look very sick, and young flocks can see high death losses when kidney-form IBV strikes. Mortality in typical respiratory cases is low (around 5%), but nephropathogenic strains can push mortality much higher (25–60%, or even more if complicated by bacteria).

In mild IB outbreaks, signs may last only a week. But co-infections (with bacteria like E. coli, Mycoplasma, etc.) or kidney strains worsen the disease. Overall, IBV infection causes clear respiratory illness and often serious production losses in poultry flocks.

What are the Effects of IBV on Human Health?

Importantly, IBV does not infect people. It is an avian virus only known to infect birds. There have been no reported human cases of infectious bronchitis. Health experts emphasize that avian IBV “has no known human health significance,” and people cannot catch IBV from chickens. In practical terms, this means poultry workers and consumers are not at risk of getting sick from IBV. Safe handling and proper cooking of poultry products follow general food safety rules, but IBV poses no direct threat to humans.

How is the Disease Diagnosed?

Because many chicken diseases cause similar respiratory signs, diagnosing IBV requires laboratory tests rather than visual inspection alone. Veterinarians confirm IBV by detecting the virus or the bird’s immune response to it. For example, lab tests can check swabs of the respiratory tract for IBV genetic material or test blood for rising antibody levels. These tests distinguish IBV from other diseases like Newcastle disease or avian laryngotracheitis (which have overlapping signs). In short, a history of respiratory illness or egg drop in a flock prompts lab confirmation of IBV by virus or antibody detection.

What Are the Prevention and Control Methods for IBV?

There is no cure for the virus itself, so control focuses on prevention and supportive measures. Two pillars of control are vaccination and biosecurity.

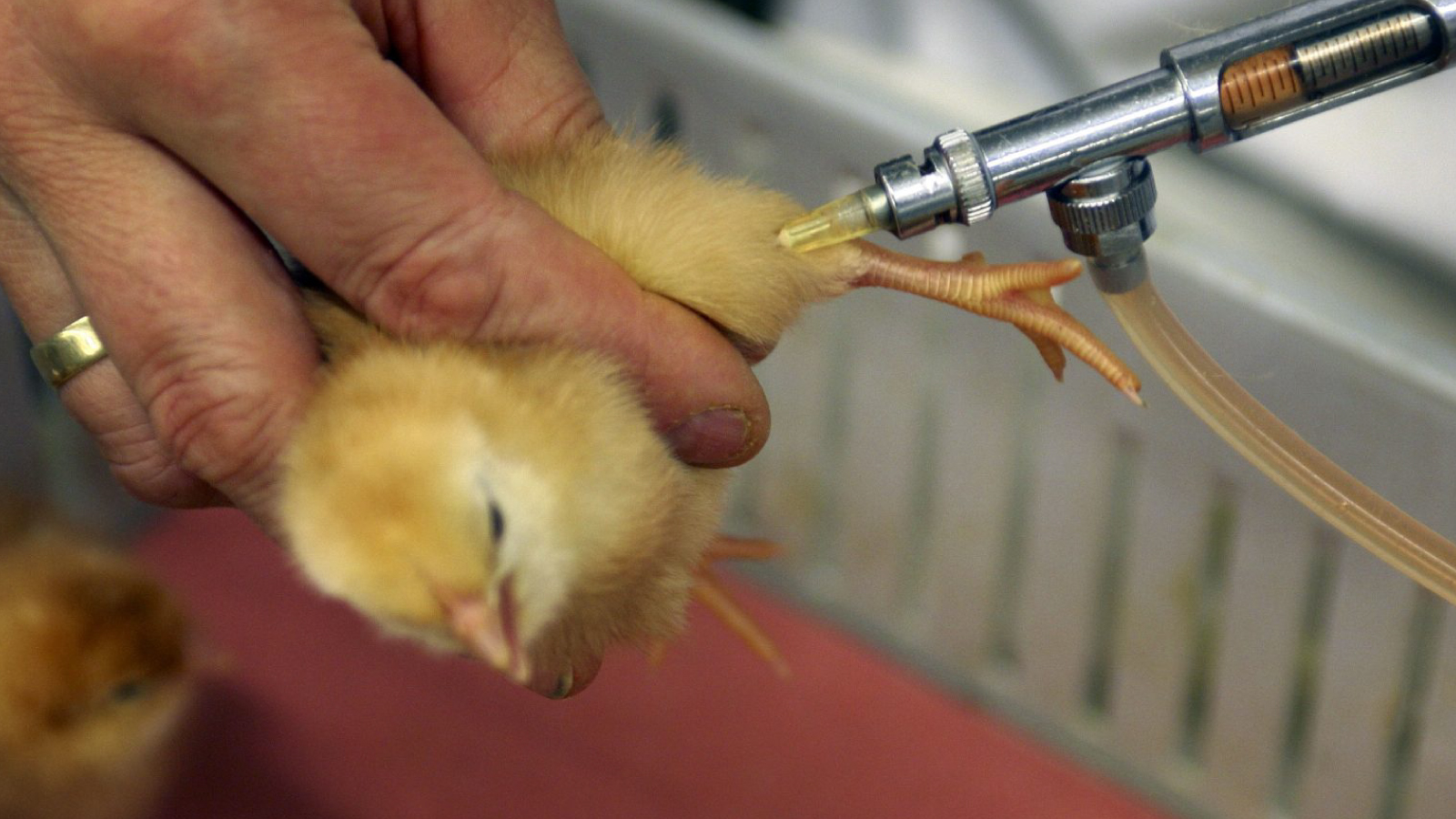

In many regions, almost all commercial flocks are routinely vaccinated against IBV. Live attenuated vaccines (given by spray, drinking water or eye drop to day-old chicks) and inactivated (killed) vaccines are used to stimulate immunity. Layers and breeders typically receive booster shots (sometimes of a different strain) a few weeks after hatch to build broader protection. Because IBV strains change rapidly, vaccines must match local virus types as closely as possible. Farmers and vets choose vaccine types based on knowledge of which IBV variants are circulating in the area. Proper vaccination can greatly reduce disease severity, but it does not eliminate the need for other measures.

Source: www.kaercher.com

Strict hygiene is essential because IBV spreads so easily. Poultry houses and equipment should be thoroughly disinfected between flocks. IBV is an enveloped virus that is killed by common disinfectants and heat (for example, 56 °C for 15 minutes inactivates it), so cleaning and drying coops, tools, and waterers helps stop the virus. Farmers should control access of people, vehicles, and equipment to chicken areas, keep poultry pens free of rodents or wild birds, and avoid cross-contamination between flocks. New chickens or hatching eggs should be quarantined and sourced from IBV-free flocks whenever possible.

Good management (adequate ventilation, temperature control and nutrition) helps birds resist disease. If an outbreak occurs, raising the coop temperature slightly can reduce stress and losses. There is no antiviral drug for IBV; care is mainly supportive. Farmers treat secondary bacterial infections with antibiotics and provide electrolytes or vitamins if needed. Diseased flocks should be isolated to prevent spread. In severe outbreaks, some producers may depopulate affected houses to protect other flocks.

By combining vaccination with these hygienic practices, farmers greatly reduce the risk and impact of IBV. For example, ensuring hatchery chicks receive maternal antibodies from vaccinated breeders and then getting early chick vaccines creates overlapping immunity. Monitoring flocks and responding quickly to any illness (with vet advice) is also key to controlling IBV on farms.

Source: poultryworld.net

What Are the Important Recommendations to Prevent IBV?

Use IBV vaccines as recommended for your region and flock type. Administer the first vaccine to chicks in the first week of life and give follow-up (booster) vaccines in young pullets and layers, using strains that match local IBV types.

Quarantine new or returning birds before adding them to a flock. Control people, vehicles, and equipment entering poultry areas. Disinfect boots, clothing, and tools between barns. Prevent contact with other flocks or wild birds.

Regularly clean and disinfect poultry houses, feeders and drinkers. Remove manure and dry litter thoroughly. Remember that IBV is killed by heat and many disinfectants, so routine cleaning breaks the chain of infection.

Check birds daily for any breathing problems or drop in feed intake. If birds become sick, isolate them immediately and consult a veterinarian. Early detection and isolation limit spread within the flock.

Provide good ventilation, proper lighting, and a balanced diet. Reduce stressors (extreme heat, overcrowding, dusty conditions) that can make infections worse. A healthy flock is more resistant to disease.

For egg producers, watch egg quality. Discard eggs with broken or very thin shells. Remember that reduced egg production and shell quality often signal IBV infection.

Although IBV does not infect humans, practice standard hygiene (wash hands, keep poultry areas clean). Ensure all poultry products (eggs, meat) are properly cooked before eating.

By following these steps, farmers can greatly reduce the chance of an IBV outbreak. Good vaccines and strict biosecurity are the cornerstones of prevention. Consumers should also know that IBV poses no risk to people; poultry products from vaccinated, healthy flocks are safe to eat. Vigilance and preventive measures are the best defense against this rapidly spreading poultry disease

References:

- https://www.merckvetmanual.com/poultry/infectious-bronchitis/infectious-bronchitis-in-chickens

- https://www.woah.org/en/disease/avian-infectious-bronchitis/#:~:text=Avian%20infectious%20bronchitis%20,Infection%20of%20the

- https://www.infectious-bronchitis.com/infectious-bronchitis-disease/epidemiology/#:~:text=The%20infectious%20bronchitis%20virus%20,turkeys%2C%20pheasants%2C%20quail%20and%20partridges

- https://extension.psu.edu/infectious-bronchitis-in-chickens#:~:text=Because%20many%20backyard%20flocks%20are,Restrict%20the%20movement%20of%20equipment

- http://extension.msstate.edu/publications/infectious-bronchitis-commercial-chickens#:~:text=Clinical%20signs%20of%20IBV%20include,Unfortunately%2C%20these%20are%20the